A large Coho hen (female) whose tail has been worn white from digging the large redd that surrounds her. Above her is a smaller jack (2 yr. old male) eagerly waiting to fertilize her eggs.

By Colton Dixon

December 13, 2018

November in California’s coastal streams means the return of salmon and steelhead from the ocean to the Russian River and its tributaries. With the arrival of fall rains, our native salmonids—steelhead trout, coho and Chinook salmon—can once again access the creeks in which they were born. These fish are anadromous, which means they are born in fresh water, move to salt water and return to fresh water. Most fish would die if they transitioned like that.

Our native salmonids spend one to three years at sea, depending on the species. There they grow much bigger than would be possible in a creek, thanks to the bounties of the ocean.

Salmon (coho and Chinook) are semelparous which means they reproduce only once. So when they enter fresh water, it means die or spawn…then die. Steelhead trout are iteroparous, which means they can reproduce multiple times. After a steelhead spawns, it turns around and heads back to sea and may return to spawn again.

Return to the river

Salmon have an amazing ability to return to the river where they were born, using a mixture of smell and magnetic fields to help them hone in to their natal creeks to spawn. Females seek out areas with the right-sized gravel and little fine sediment to build their nests. There can be competition between females for prime spots and males will often battle fiercely for the opportunity to spawn. When salmonids spawn they dig a nest for their eggs to incubate in. This nest is called a redd. Why is it called redd? Is it because salmon eggs can be reddish in color? Maybe?

The word ‘redd’ originates from a Scottish word that means, “to clean an area or make it tidy”. A female salmon will use her caudal (tail) fin to dig a depression in which to lay her eggs, then clear a patch of larger rocks to cover them. This is interesting because often a redd looks like a “clean” spot in the creek bed, at least before a large storm event comes through and cleans the streambed.

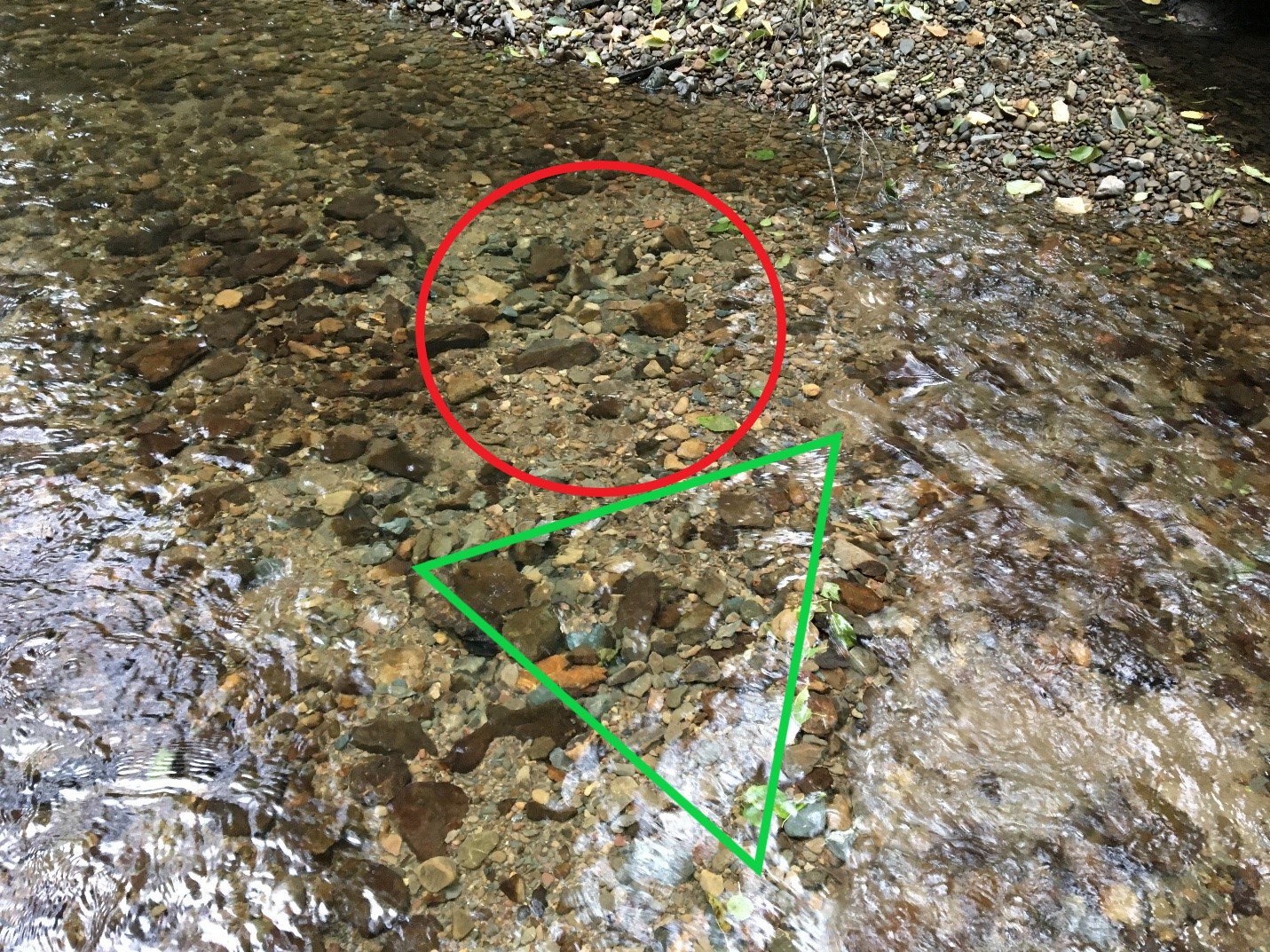

A classic coho salmon redd, the red circle is the pot and the green triangle is the tail spill

Redds can be described as having two parts; a pot and a tail spill. The pot is a depression dug out by the spawning salmon. The tail spill appears as a fan of gravel downstream from the pot. In the tail spill can be a series of pockets where the eggs (up to 4000!) are buried by substrate from the pot. The tail spill acts as a small riffle, where streamflow moves oxygenated water over the developing eggs and removes sediment and waste products from the young alevin (tiny fish with a yolk sac attached to their bellies). This behavior is fairly unique for fish, since burying eggs is considered parental care—and it doesn’t stop there!

A female will guard her redd ‘til she dies, which can be up to 10 days after spawning! The eggs and alevin stay in the redd for about 70 days. It is during this time that salmon are at their most vulnerable and where the most mortalities occur.

An inside look of alevin and eggs inside a redd tail spill. (photo credit: E. Peter Steenstra, Creative Commons)

Watch your step

It is absolutely critical to watch where you step if you find yourself walking in streams during spawning season, which in the Russian river watershed is November-April. Even though eggs harden during the incubation process and the alevin are buried under rocks, a footstep can easily compact the rocks and kill eggs and juvenile salmon. Often times fish will spawn in shallow water, about 1-3 feet deep.

Our local salmonids prefer to spawn at the tail-outs of pools (downstream ends) or in lower gradient riffles with a dispersed flow. These sections of creek are usually the easiest spots for us to walk, so be careful! Redds can also be buried by silt, which starves eggs and alevin of the oxygen they need. While some siltation is natural, a lot more occurs as a result of human activities, like road building and removing riparian vegetation. Warm water, and low streamflow, which can leave redds high and dry, are also threats to salmon reproduction.

Coho, Chinook and steelhead trout are amazing animals that we are very fortunate to have spawning in the Russian River watershed! Just two decades ago, coho were nearly extirpated from the system. Thanks to the impressive efforts of many agencies, volunteers and concerned landowners, not only was extirpation avoided but we are seeing increasing returns of these fish! As we welcome another year of spawning adults, let us be extra mindful of redds and ensure that these keystone species have the most success possible by being conscientious and minimizing our impacts on them.

A steelhead hen (female) digging a red with a buck (male) guarding her.

Now that you are a master of the redd, can you see the redd? The pot? Tail-spill?