Paloma Aguirre began working in conservation because of her love for surfing. Now, she manages funding for environmental nonprofits across Latin America and addresses local problems in Imperial Beach, California as a city councilmember.

By Erin Malsbury, 2020 California Sea Grant/UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Intern

Paloma Aguirre emerged from the tunnel of a curling wave on a bodyboard with a new life purpose. Many surfers describe “getting barreled”—gliding between flowing walls of water—as a nearly spiritual experience. An ocean devotee’s baptism. The first time it happened to Aguirre, she was hooked. “I realized that surfing and the ocean were my passion,” she says.

Her love for the water drove her to become an advocate as well as an athlete. Now head of the nonprofit International Community Foundation’s environment programs, Aguirre oversees funding for more than 80 conservation nonprofits in Mexico and Latin America. In 2014, she was named Woman of the Year by California State Assembly member Lorena Gonzalez for her work conserving and restoring the Tijuana River Valley. She went on to earn a master’s in marine biodiversity and conservation from UC San Diego and work as a Knauss Legislative Fellow on Capitol Hill. And for the last two years, Aguirre has moonlighted as a city council member for Imperial Beach, California, fighting to protect residents from threats such as water pollution and sea-level rise.

“Paloma is an absolute charger,” says Serge Dedina, mayor of Imperial Beach. He met Aguirre more than a decade ago while surfing and became her boss and mentor at WILDCOAST, a non-profit focused on conservation at the US-Mexico border. “I just have an image of Paloma charging into a hollow wave, getting completely barreled, coming out and doing a 360 in the air and just landing it,” he says. “She has that same attitude as a conservationist and an elected official.”

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and a local housing crisis, Aguirre has widened her focus from conservation. She currently leads the high-risk populations sub-committee on the city’s COVID-19 task force. “Those people in my community that have no one, or no financial resources, or no help—I want to make sure that they make it through this terrible situation in a safe way,” she says. “That’s what I’m focused on right now.”

But it all started with surfing.

Tides Turning

Aguirre remembers watching surfers as a little girl in San Francisco, where she was born. “But it always seemed like it was something far away or out of my reach,” she says. After her family moved to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, people told her that surfing wasn’t for girls. She taught herself anyway, becoming the first girl in her town to surf and, eventually, one of Mexico’s best bodyboarders. In 2012, she came in second place in the bodyboarding division at the Mexican National Surfing Championships.

Aguirre rides a bodyboard in Imperial Beach, CA. Photo credit: William Bay

Aguirre started her studies in Mexico wanting to be a psychologist, but her time in the water led to a passion for protecting the environment. “Everything I do and who I am revolves around my love for the ocean,” Aguirre says. “So in a weird way, it's self-interest that I've ended up being a conservationist—because I want to take care of what I love the most.” She moved to Imperial Beach, California, the most southwestern city in the United States, and transferred to the University of Southern California in 2003, working two jobs in order to become the first person in her family to graduate from college. Aguirre immediately fell in love with Imperial Beach and took two buses and a trolley to get to school every day rather than move anywhere else.

In 2005, she started volunteering for WILDCOAST, an international organization that aims to conserve marine and coastal ecosystems. She focused on improving water quality along the United States-Mexico border and worked her way up to program coordinator, then manager, then US-Mexico border director. She cut her hours back in 2014 to earn a master’s degree in marine biodiversity and conservation from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego.

From advocacy to policy

After finishing her master’s, she jumped at the chance to work on national environmental policy in Washington DC as a California Sea Grant Knauss Legislative Fellow. “I've always been kind of a policy wonk,” she laughs. On Capitol Hill, she advised Senator Cory Booker on environmental and climate change issues. The environment was electric. “You're pushed into situations where you have to just drink from the firehose and do your best,” she says. “Trial by fire.”

Aguirre spent a year in D.C. working alongside policy makers as a Knauss Legislative Fellow. Photo credit: Gurpreet Bhatia, US Capitol, Washington, D.C.

By the end of the year, Aguirre had helped move forward several environmental acts. One piece of legislation, the Marine Debris Program Reauthorization Act, funded efforts to find and remove sources of garbage from the ocean. Another — an executive presidential memorandum — called for more diversity within Department of the Interior agencies such as the National Parks and National Forestry services. “Being on the other side of the coin — not being the advocate, but the office of a member of the Senate — gave me a different perspective and gave me confidence that I can really make a positive change,” she says.

Aguirre loved the work so much that she and her husband considered staying in Washington D.C. with their two enormous dogs. But severe pollution in the Pacific called them back to Imperial Beach. Between 2015 and 2020, the city’s beaches had been closed almost 50% of the time, mainly due to sewage and plastic pollution that flowed across the border from Tijuana.

Aguirre returned to WILDCOAST as director, advocating for conservation policy and water quality funding at the state and federal level. She organized letter-writing campaigns, met with members of Congress, and worked with local government to address the water pollution problems—some of the worst in the state.

Aguirre and Jared Blumenfeld, Secretary CALEPA, walk through trash at Dairy Mart Road Bridge, Tijuana River Valley, U.S. Photo credit: Fay Crevoshay

Aguirre and WILDCOAST went beyond simply calling out issues, says David Gibson, executive officer at the San Diego Water Quality Control Board. They offered ideas for change. And Aguirre was a rare voice of authority on both sides of the border, he says. Her perspective caught Gibson’s attention when they met just over ten years ago. “She wants water quality for everyone,” he says—not just Imperial Beach residents, but also other communities, agriculture and wildlife. When asked how he would describe Aguirre, Gibson didn’t need time to think: “Fearlessly passionate.”

So passionate, in fact, that a few years ago she found herself blacklisted by the governor of Baja at the time. She had led an exposé of a defunct sewage treatment plant less than ten miles from Imperial Beach that was pumping 40 million gallons of raw sewage into the ocean every day. The governor had insisted the facility wasn’t a problem.

“These lagoons were just black, putrid, toxic muck,” Aguirre says, recalling a visit to the plant. “There were huge clouds of flies all over you... you couldn’t even breathe.” The plant’s technology was archaic and had been dysfunctional for nearly two decades, she says. The story made national news, and Baja’s administration refused to meet with Aguirre. Dedina recalls her reaction to being blacklisted as “‘Oh well. I did my job.’”

In 2019, Aguirre left WILDCOAST to oversee the environment program at the International Community Foundation (ICF). Unlike what she calls her “water-proof boots on the ground” work at WILDCOAST, at ICF Aguirre takes a 30,000-foot view of conservation issues. She coordinates funding and projects across Mexico and Latin America. Now, she only breaks out the boots for her city council work.

Aguirre discusses beach closures and how they affect Imperial Beach on KUSI News. Photo credit: Fay Crevoshay

Setting sights on city council

After watching her long-time mentor Dedina win a campaign for mayor of Imperial Beach, she started considering whether she could run for city council alongside her conservation work. “I thought, ‘Well, if he can do it, I can do it too,’” she says. Aguirre began building a grassroots campaign to run for city council, confident that she could use her environmental policy skills to clean up Imperial Beach.

But running for office was tough.

“I can’t tell you how many things were made up about me,” she says. “It was relentless.” People posted flyers on the street calling her anti-American and anti-veteran because she had posted a photograph online of a woman at the 2016 Women’s March holding a sign that she thought was funny: “Make America Mexico Again”. But Aguirre says, “the scary part was not so much the slander and libel, but the threats that were made to my safety and life.”

Unlike in larger races, there were no polls and no hints about her standing among voters. The night before the election, Aguirre recalls thinking, “‘What if I lose? What if they win? What if all those lies that they've been spreading about me actually influence the election and change people's mind, and all of our hard work is just down the drain?’” And the election process was slow. Because of mail-in ballots, it took almost a month to find out the result. Aguirre didn’t come in first place in the first batch of ballots.

“But then, as the days went on,” she says, “I started to rise, rise, rise.” She won, becoming the first Latina elected to office in Imperial Beach. “I think that is one of the proudest moments of my life,” she says.

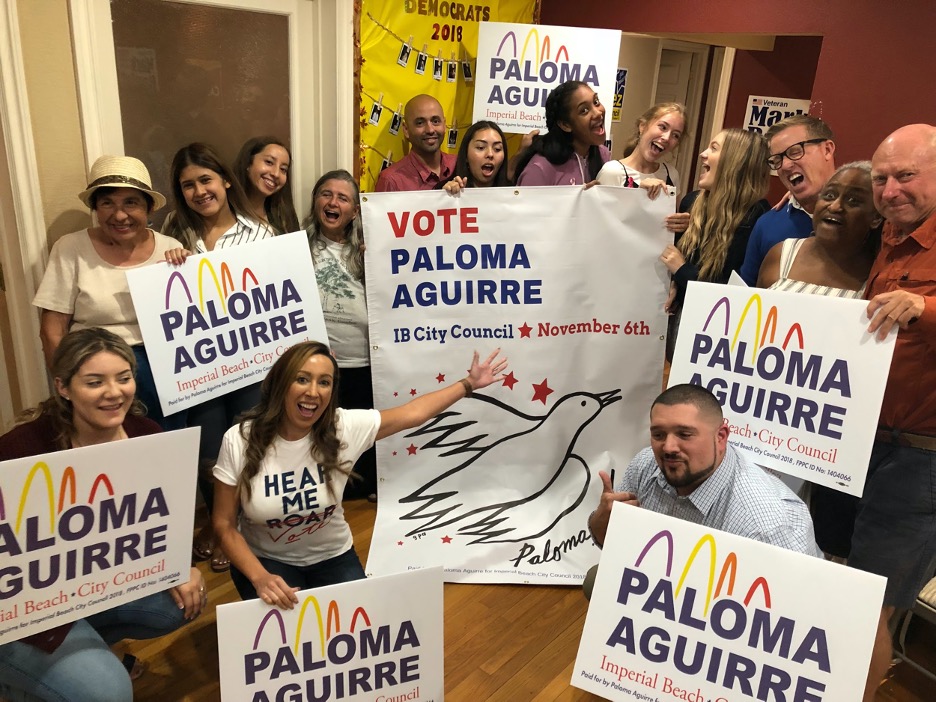

As a city councilmember, Aguirre focuses on issues that range from clean water to affordable housing. San Diego’s Southbay Democratic Party Election Headquarters, Chula Vista, CA

Local impact

In addition to becoming known for her environmental work, Aguirre is also developing a reputation as someone passionate about housing issues, Dedina says. She’s “making sure that our most underserved and neglected residents are heard from and participate in the decision-making,” he says. Aguirre says her background helps her connect with these community members.

“I know what it is to struggle and not have a lot of money and be kicked out,” she says. The number one issue in Imperial Beach is water quality, she says, “but the number two issues is housing.” One of the highlights of her time on city council so far has been successfully pushing for the city to hire a housing specialist who attends to renters’ rights issues. In the midst of COVID-19, Imperial Beach was also one of the first cities in the area to pass a moratorium on evictions for renters. Aguirre says she finds comfort in the fact that residents can at least feel secure about the roof over their head.

No matter what issue she’s tackling, Aguirre keeps science-informed policy in mind. “It’s everything — especially right now,” she says. To combat what she calls a “cold war against science,” Aguirre often has to push back against conspiracy theories and hoaxes, such as climate change denial. “We’re seeing it everywhere,” she says. “Not just at the federal level, but especially here locally.”

She describes the challenge of developing a coastal plan to address sea-level rise with an incredulous laugh. Even after numerous public meetings, reports, educational and outreach efforts, and presentations by experts, she says, “you still have a small faction of — very small but very vocal — dissenting voices.” People make jumps, she says, from “Oh, you’re planning on moving some of your public infrastructure that’s on the coast to protect it, to You want to take my home by eminent domain, so therefore, I completely oppose anything you put in this plan that relates to sea-level rise. Sea-level rise isn’t even real. You’re making that up. Floods have occurred for centuries, and this is nothing but a yearly flood.”

These conspiracies are particularly dangerous for Imperial Beach because water surrounds the city. Sea-level rise is a real threat. After showing people the science, “if some folks don’t want to come along with you, well, there’s not much you can do,” she says. “I think sometimes it takes political, not just will, but courage to know that you are basing your decision not just on the feedback from your community, but also on science and facts.”