Pacific oysters are colonizing the San Diego Bay coastline, and new research shows that they may not always be safe to eat

A new study published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin examines the risks of consuming wild harvested oysters from San Diego Bay. Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas), an Asian species brought to the west coast for aquaculture, has been colonizing the coastline of southern California in recent years. The farmed delicacies, which are rigorously regulated and tested for safety, are shucked from their shells and served in restaurants around the world, but after growing up in an urban bay, are they safe to eat?

“We see feral Pacific oysters cropping up more and more in coastal bays in the area, and they can get big, just like what you would get in a restaurant,” said Theresa Talley, the California Sea Grant Extension Specialist who co-led the study. “There were a lot of studies on contamination in finfish, but there was this gap of knowledge for shellfish.”

Shellfish, like oysters and mussels, eat by filtering small food particles from the water, which can lead to bioaccumulation of contaminants and makes them good environmental indicators. The state had been monitoring contaminant levels in mussels up until 2003, when the California State Mussel Watch Program ended due to funding challenges.

To fill this research gap, Talley teamed up with Chad Loflen of the California Regional Water Quality Control Board, San Diego Region (San Diego Water Board), and David Pedersen, an anthropologist at the University of California, San Diego. With funding from California Sea Grant and SWAMP, California’s Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program, the project team sought to build on these data by including feral Pacific oysters and emerging chemical contaminants, such as microplastics, phthalates, newer pesticides and pharmaceuticals. The team also wanted to collect data to update existing guidelines for consuming fish and shellfish from San Diego Bay (see A guide to eating fish from San Diego Bay).

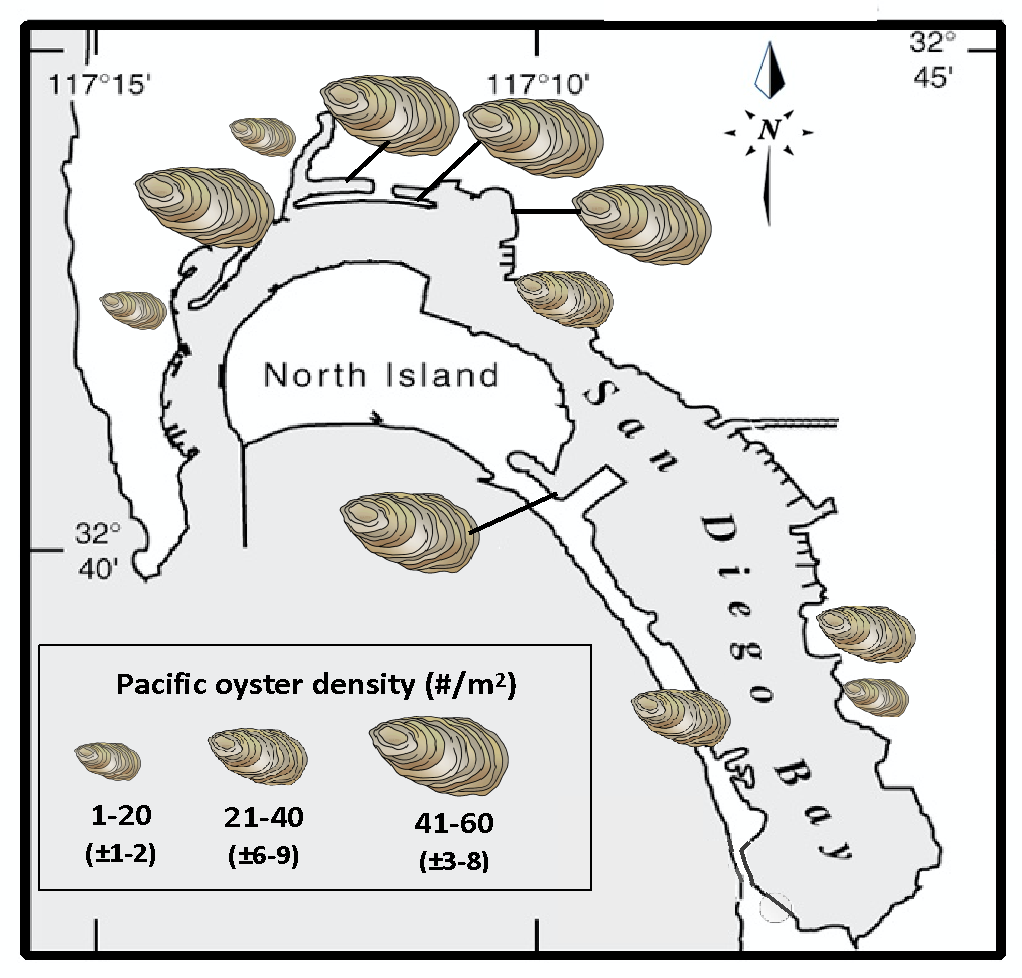

Map of San Diego Bay showing location and density of Pacific oyster colonies.

The researchers set out to understand where the oysters were colonizing and the types of contaminants they carried across seasons. They visited 11 sites in San Diego Bay in summer 2018 and winter 2019 to collect oysters and examine their contaminant concentrations. Much of the San Diego Bay shoreline is lined with large rocks to reduce the eroding impact of wave action: Pacific oysters are spreading across the higher tidal elevations of this new habitat and are now the dominant species found.

Concentration levels for a total of 165 compounds were measured, and oysters at every site surveyed showed a wide range of contaminants. Oysters in all sites sampled through the year had anywhere from 7 to 11 types of contaminants. Summer brought with it high levels of PCBs and pesticides. Some compounds that bind with sediments and plastics were more abundant in the winter. At some locations, the winter increase in plastics per oyster more than doubled compared to summer samples. According to Talley, with the winter comes rains causing runoff and flows that move the contaminated sediments and larger particles like plastics from upstream into the bay.

“With climate change, we have these longer droughts where pollutants build up on the roads,” Talley said. “Then all of a sudden a big torrential storm hits, and where does it all go? It washes down through the storm drains into the bay.”

The good news is that some of the older, banned contaminants, such as tributyltin, mercury, and DDT, seem to be relatively low in the oysters. Other contaminants, like copper and zinc, were elevated compared to historic mussel data. This may be linked to changes in use, as copper replaced tributyltin as a boat bottom paint and both copper and zinc are found in– and subsequently released from– car brake pads and tires. There were also detections of newer compounds, such as neonicotinoid and pyrethroid pesticides.

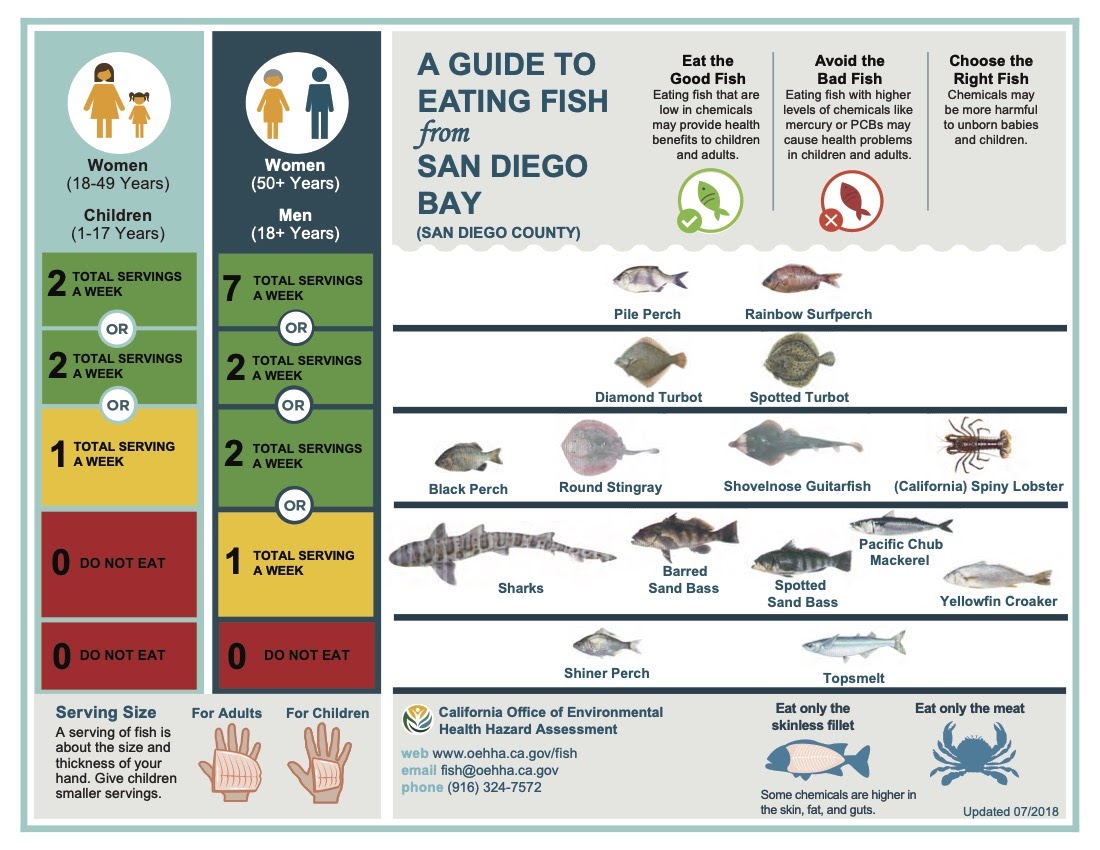

OEHHA’s fish consumption guidelines for San Diego Bay.The health effects of many of the emerging contaminants are only starting to be realized leaving us a ways off from having consumption guidelines for these compounds. As for the consumption guidelines we do have, the oysters were below some, but not all, published thresholds. The baywide average PCB concentrations in the oysters fell into a “one to two servings per week” guideline for adults while concentrations in some individual sites were above a “Do Not Eat” threshold. Some oysters also were above thresholds for PAHs, including Benzo[a]pyrene (BAP). Another area of uncertainty is the additive health effects of different contaminants—even those that fall below thresholds on their own but together may have uncertain health impacts.

The range in oyster contamination between seasons and specific locations makes it difficult to make sweeping advisories in the San Diego Bay, according to Talley.

“You can't just look at Bay-wide data and say, ‘here's the average, it's safe.’ You need to consider location, season, species and what the maximum values are,” adds project co-lead, Chad Loflen. “The results show the need for longer-term monitoring efforts to both assess risks to consumers and also track improvements in the bay over time as pollution controls are put into place.”

Contaminant levels in San Diego Bay, like many urban bays in the country, are improving with efforts from State and local agencies. For instance, most recently, the San Diego Water Board has required the cleanup of 13 locations in San Diego Bay, which has resulted in the remediation of nearly 500,000 cubic yards of contaminated sediment, while also requiring actions be taken to eliminate landside sources, particularly for banned chemicals like PCBs. While cleanups have traditionally focused on industrial areas as pollution hot spots, this study confirms that pollutants and contaminants are transported via the food web throughout San Diego Bay. It’s heartening to see that levels of some banned chemicals, like the historic pesticide DDT, are low, but more information is needed on newer contaminants like neonicotinoid pesticides and microplastics.

In addition to the clean-up efforts at industrial sites, the San Diego Water Board is also working with local Tribes and subsistence anglers to improve fishing conditions. This initiative will strive to address concerns about environmental justice by considering the designation of areas throughout the San Diego Region, including San Diego Bay, for tribal beneficial uses and subsistence fishing. The Board is also conducting a pilot study in partnership with Tribal representatives and stakeholders to better characterize pollutant concentrations in species of concern to Tribes and subsistence anglers, including in San Diego Bay.

Studies like this one are critical for understanding what chemicals exist in the environment around us and are impacting food and water sources. This study confirmed that Pacific oysters are important for assessing the fish and shellfish consumption beneficial uses of San Diego Bay water, and they are included in the San Diego Water Board’s Unified Assessment and Strategic Monitoring Approach for San Diego Bay released in December 2021. With this information, scientists can examine the health effects and pass this information on to managers and policymakers.

Theresa deploying a fishing net.

“For the project team, engaging with community members will be an important next step in helping us craft guidelines, management actions, and other solutions,” Talley said.