Restoring Southern California’s urban canyons helps protect ecosystems, wildlife, and open space for urban residents. Restored, native canyons could also be crucial in making communities more resilient to the impacts and risks of climate change, according to a new report led by Theresa Talley, a California Sea Grant extension specialist based at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

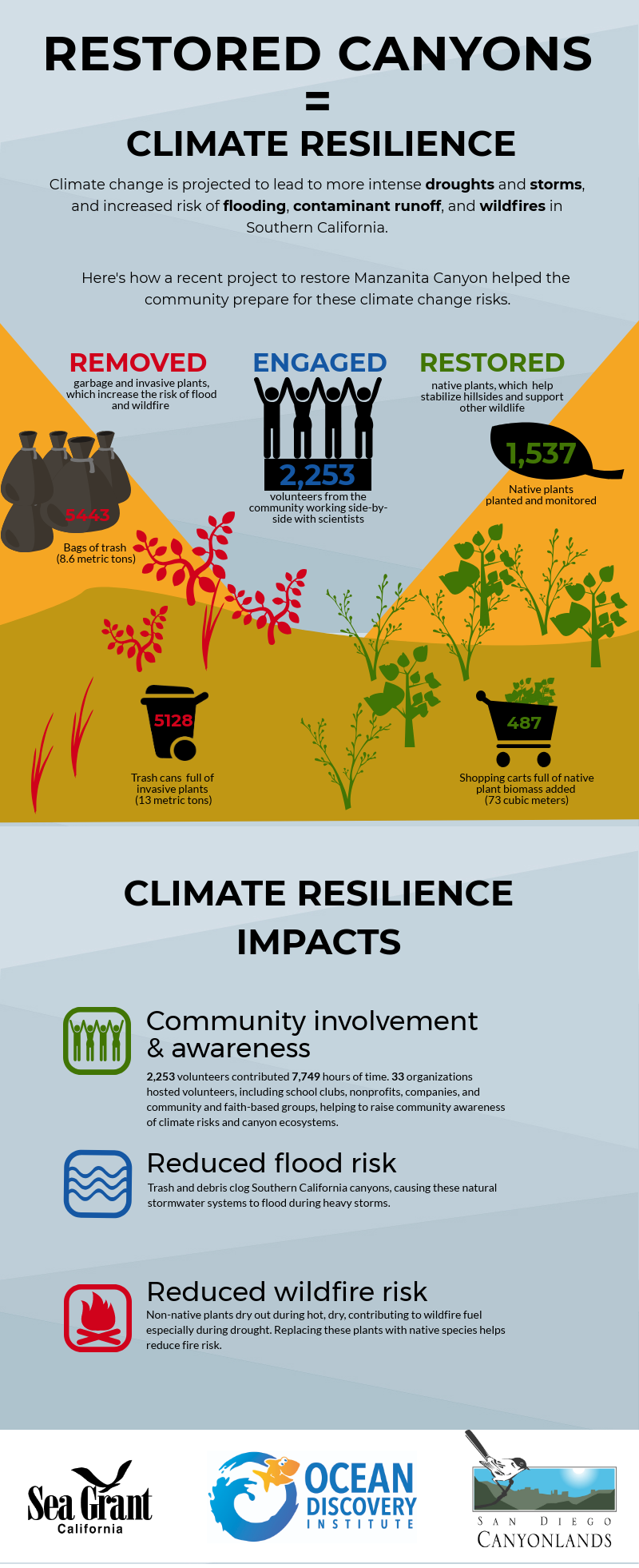

During the two-year project, volunteers removed 22 metric tons of invasive plants and trash from San Diego’s Manzanita Canyon, and planted and monitored 1,537 native plants. The project, a partnership between California Sea Grant, the Ocean Discovery Institute, and San Diego Canyonlands, engaged 33 community groups and 2,253 volunteers, who gained an understanding of their urban watershed and climate hazards.

Over half of the people who came out to lend a hand were from the City Heights community, and over half were kids getting outside with their families, clubs and school classes to learn more about science and the ecosystems in their backyards.

“In a highly urbanized community like City Heights, having clean, safe open spaces, like canyons, is so important,” says Joel Barkan, Research and Restoration Manager at Ocean Discovery Institute. “They enable kids and families to explore nature and build curiosity about the environment. This project empowered the community to take ownership of Manzanita Canyon by restoring the habitat and keeping it clean.”

The restored canyon ecosystem will help make the canyon, and the community surrounding it, more resistant to floods, water contamination, and wildfire—risks that are projected to increase as climate change brings higher temperatures and more extreme rain events. The project also provides data and lessons that could help guide future restoration efforts.

Manzanita Canyon restoration plot before planting in May 2016 (left), and six months after planting in May 2018 (right). <br> Credit: Theresa Talley

A natural storm drain

Manzanita Canyon is a 0.6-mile-long canyon bordered by two freeways and San Diego’s City Heights neighborhood, a diverse community with high poverty rates.

“Manzanita Canyon is an island of nature in the middle of an urban landscape. It’s a refuge for wildlife, and an escape for people. If you walk down into the canyon on a hot day, the temperature drops by a couple of degrees, and you’re surrounded by dense vegetation that has the pleasant aroma of the Coastal Sage Brush.” says Eric Bowlby, Executive Director of San Diego Canyonlands. “You begin to see wildlife, like rabbits running to hide, and you hear a greater variety of birds.”

As part of a network of over one hundred canyons within San Diego city limits, Manzanita Canyon helps link the city to the ocean.

“Our canyons are the heart of the City’s stormwater system,” says California Sea Grant Extension Specialist Theresa Talley. “Whatever is on our streets, flows into our canyons. And whatever is in the canyons can get washed down to the bay or the ocean when it rains.” The canyon’s plants and soils can filter water as it flows through, helping to clean it before it reaches the ocean. But the high levels of trash and debris that we have been seeing can be too much to filter, and can clog up the drainage system, leading to flooding when heavy rains come. Invasive plants and trash in the canyons also increase the risk of fire, which can spread to surrounding communities.

Climate change in the canyons

While there are plenty of reasons to clean up trash and restore native plants in San Diego’s canyons, climate change makes restoring these essential watersheds more urgent.

Climate change is projected to bring increased temperatures, more days of extreme heat, and more concentrated and intense rainfall in San Diego. These impacts increase the vulnerability of communities bordering San Diego’s urban canyons and the canyons themselves. Restoring native plants, and removing fast-growing annual plants and garbage can help reduce vulnerability, explains Talley. At the same time, involving communities in restoration can increase understanding of climate-related hazards, helping to build community resilience.

Click to view photo album on Flickr.

The science behind canyon restoration

The project also went a step beyond most restoration projects: researchers and community volunteers meticulously tracked, measured, and categorized the trash that was removed, as well as the area of native landscape restored and the growth of native plants.

“We found that plastic made up more than half of the garbage on the canyon floor, and half of the plastic trash consisted of plastic bags and wrappers,” says Talley. The analysis also found that illegal dumping, homeless encampments, and storm drains were the major sources of trash in the canyon. Knowing where trash originates is the first step in reducing the problem at the source.

The team also tracked the survival of the native plants, finding that weeding, slope stabilization, and watering are often needed to help native plants get a foothold, particularly during periods of drought.

The project team monitored the involvement of community organizations and volunteers, finding that community engagement was most effective when community-based leaders and organizations were involved in recruitment and motivation of the volunteer effort.

The results of the project provide a groundwork for future restoration projects and efforts to increase climate resilience around San Diego and Southern California.

“The outpouring of community leadership and community participation—all centered around improving this one neighborhood canyon—was probably what impressed me the most about this project,” said Talley. “Communities like this one in City Heights give me hope that we can weather the figurative and literal storms that are associated with climate change.”

Funding for this project was provided by the California Coastal Conservancy Prop 1 Grant Program and California Natural Resources Agency Prop 84 Grant Program.