While red abalone were once abundant throughout California, they have long been in decline due to overfishing and environmental changes. This shortage has resulted in the closure of the red abalone fisheries, and a growing effort to protect and re-establish abalone populations. California Sea Grant-funded researchers identified conditions that promote consistent recruitment, but also found that prolonged heat stress can cause red abalone recruitment to fail, in a new study published in the Journal of Shellfish Research last month.

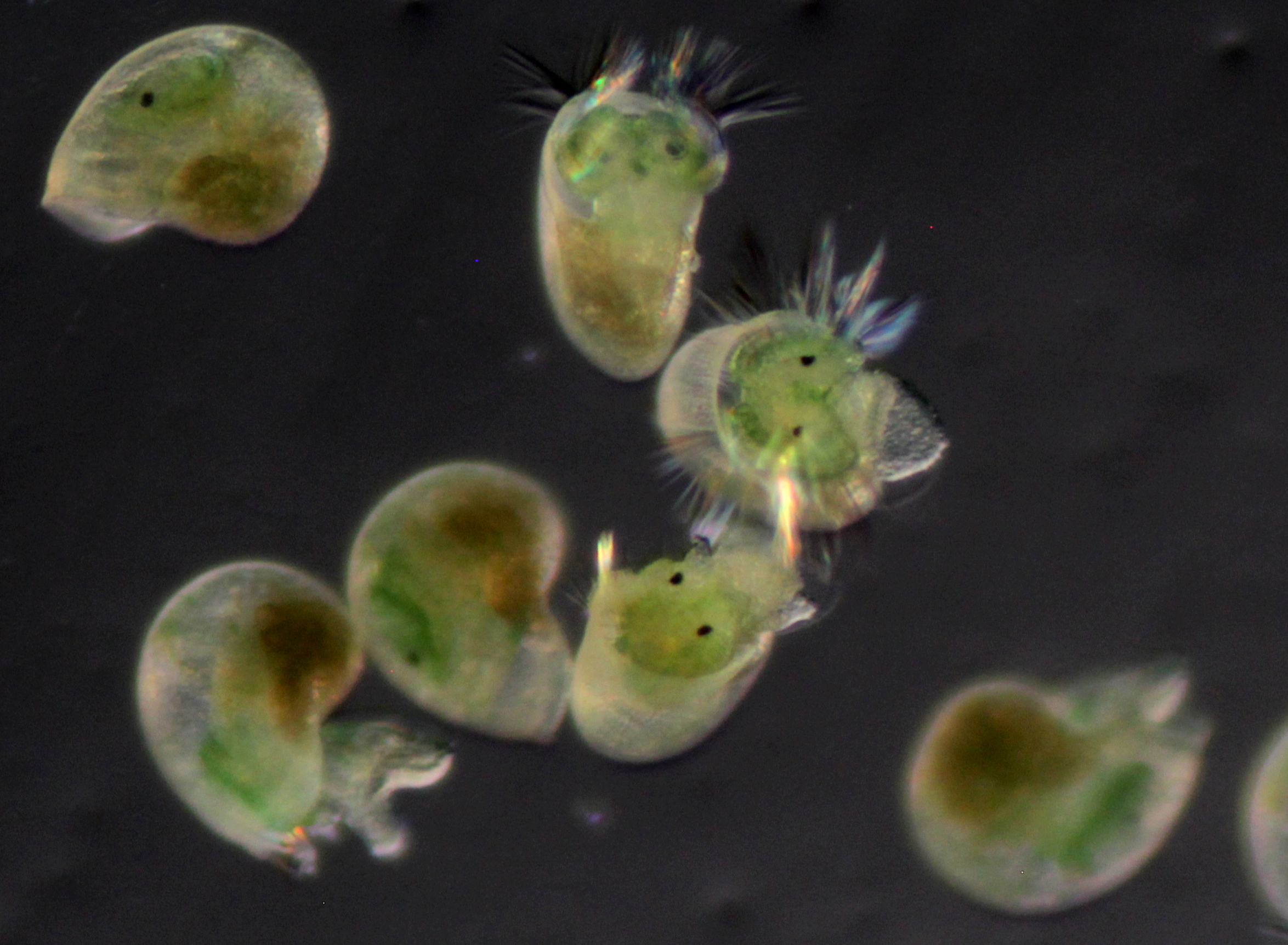

Microscopic red abalone larvae before settlement to the ocean bottom. Photo credit: Charlie BochRecruitment—the production of new young abalone—is critical to maintaining and recovering the populations of this iconic California species. The study highlights conditions in Monterey Bay which ensure consistent and adequate abalone recruitment, even when abalone populations are at low densities (few individuals for a given area). These include: abundant food (kelp) year-round, individuals aggregated together so that eggs and sperm can mix, and shelter within an embayment that helps retain larvae. However, during the course of the five-year project, “The Blob” of 2014-2015 created unexpectedly warm water in the Pacific Ocean. The researchers observed a massive decline in abalone recruitment during the second year of warming.

“This indicates that the warming did not cause death of larvae or abalone recruits, as they survived the first year, but rather caused reproductive failure after prolonged heat exposure,” says Jennifer O’Leary, who led the work as a California Sea Grant extension specialist at California Polytechnic State University (Cal Poly). “This is likely because abalone had to shift energy from producing eggs and sperm to surviving under prolonged heat.”

Newly settled juvenile abalone (<1mm in size). Photo credit: Jennifer O'Leary

Though high temperatures are a threat, “identifying the conditions that promote recruitment in low density populations is critical to inform management, now that abalone are depleted state-wide,” says Leslie Hart, lead author of the study, who started the work as a masters student at Cal Poly advised by O’Leary.

Prior research has shown that in the past, when northern California had two times as many abalone per unit area as found in central California, recruitment was not consistent from year to year. There were very good “boom” years with a lot of new baby abalone and then multiple years with little to no recruitment of young. So when the researchers started the work, they were not sure they would be able to even detect recruitment in central California, where red abalone occur in naturally low numbers due to sea otter predation.

“Nobody had ever evaluated early recruitment (two weeks to two months old) of abalone in central California prior to our study,” says Hart, who was also a 2018 California Sea Grant state fellow with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“This study demonstrates the important link between large-scale climate patterns and oceanographic variability and local ecosystem dynamics, and it offers a clue as to how future climate-change-driven ocean warming might affect vulnerable abalone populations,” explains co-author and Cal Poly Physics Professor Ryan Walter.

An adult red abalone. Photo credit: Athena Maguire

“The hope is that this study contributes to development of new management approaches to restore abalone populations,” says Maurice Goodman, who contributed to the work as a laboratory technician at Cal Poly and is now a graduate student at Stanford University.

The researchers still have a big question for the future: “What is the feasibility of the recovery of California abalone, particularly where conditions are not ideal?” Given that accumulated heat stress was a problem under this best-case scenario, the species faces serious hurdles in places like the north coast where kelp has collapsed. However, there remains hope in finding parts of the state where ideal conditions still exist, and these sites could be protected and used as recovery locations. Other management actions like aggregation of existing abalone in protected areas could give the species an added boost needed to recover.