What is California without its sandy beaches? Hundreds of millions of people visit our sandy beaches each year to escape the heat, to surf, to fish, and to take in the natural beauty of our coast. But our beaches are disappearing. And sea-level rise threatens to drown many of our beaches that don’t have the space to progress inland.

Seasonal sand berm in Venice Beach, CA. Photo credit: Jeremy Smith

Thankfully, people up and down the state have been discussing strategies to help our beaches survive through what is called regional sediment management. Sediment is the general term for particles of rock. Of course, for beaches, the magic particle is sand!

As it happens, sand particles that we find on the beach are just the right size to be moved by our ocean waves but not so small that they are swept far into the ocean by currents. Sand also feels nice for walking, playing volleyball, and laying down on to catch some sunrays. What you may not have heard, though, is that sand is becoming harder to find.

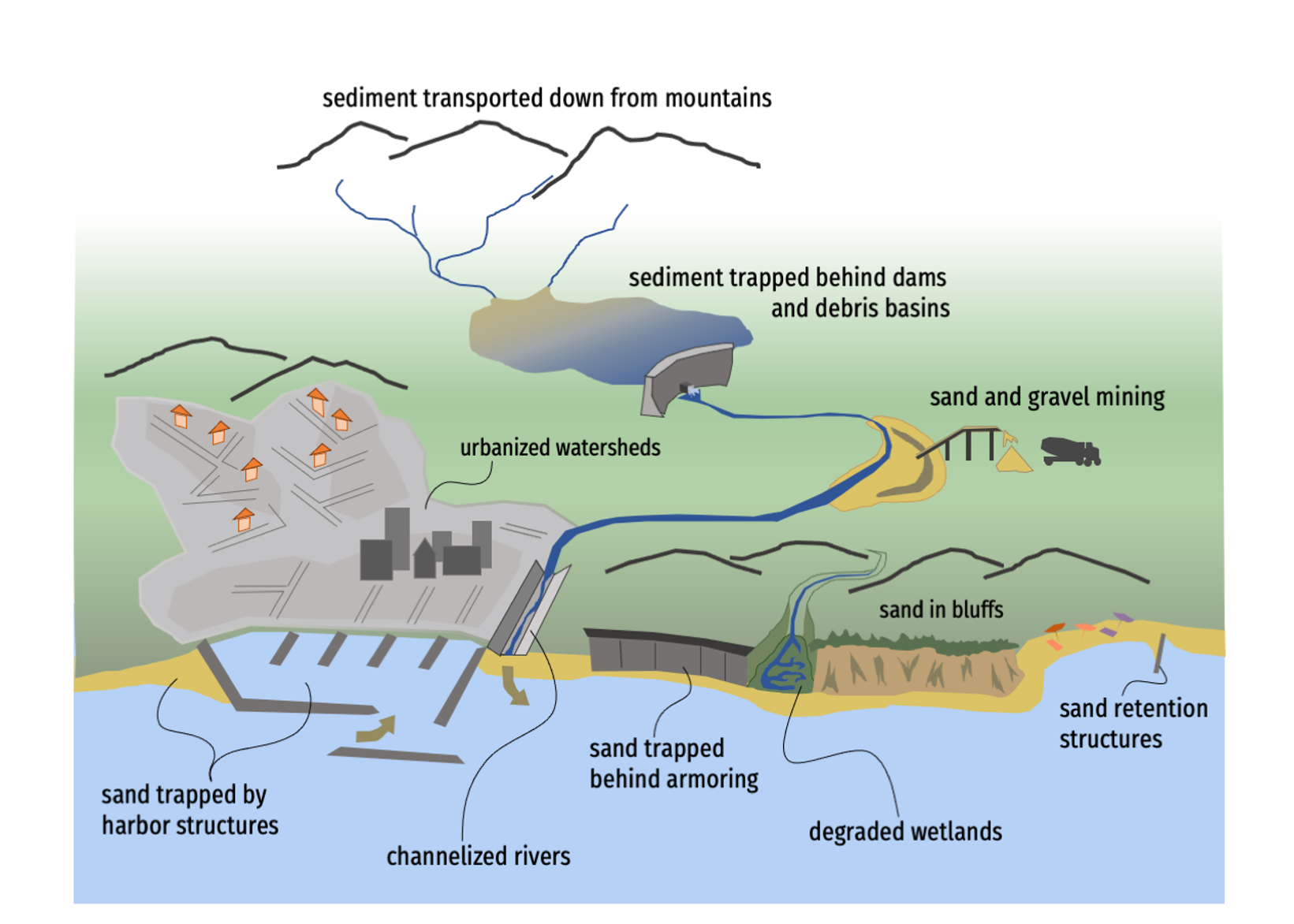

Diagram of sediment pathways. Image credit: Jeremy Smith

There are competing demands for sand; particularly “angular” grains that lock together to form stronger concrete. This sand is mined from active or ancient riverbeds and sometimes coastal dunes and beaches, not from deserts where wind weathers the sand into rounder grains. The sand on our beaches typically has arrived there after being eroded from mountains and carried to the coast by rivers or by the erosion of coastal bluffs that contain sand. The amount of sand being carried to the beach through these natural pathways can change year to year and is impacted by human activities such as the dredging of sand from harbors, damming our rivers, covering our watersheds with pavement, and armoring our coast.

It takes a lot of sand to make a beach—the beach is not just what we see above the water; it extends offshore, 30 or 40 feet below the surface. When more sand is leaving the beach than entering, the beach has a sand deficit and will “erode.” There are several pathways for sand to enter or leave a beach. It might be hard to notice when you visit the beach, but waves are constantly moving sand around; sometimes immense volumes of sand can be transported along the coast over just a few weeks!

These pathways tend to occur over large areas and almost always cross jurisdictional boundaries from city to city and county to county. Because of this, a statewide working group, Coastal Sediment Management Workgroup, made up of members from state and federal agencies, has chosen to promote regional approaches to sediment management. The hope is that individual cities and counties, as well as state and federal agencies, can come together to coordinate the restoration and augmentation of natural processes to address the sediment imbalances that cause our beaches to erode.

Some of the strategies used in regional sediment management plans include:

- Beach nourishment: acquiring clean sand from harbor maintenance dredging, offshore deposits, or upland sources and placing it on or near the beach.

- Sand retention structures: coastal structures such as groins, breakwaters, artificial reefs, or jetties that hold sand in place or slow its movement.

- Restoring natural sediment sources: removing dams and restoring the flow of sediment down rivers, removing coastal armoring so that sand can erode onto the beach, etc.

State and local governments must coordinate regionally on strategies to optimize the public benefits and to reduce detrimental impacts “downstream” or “downdrift”. These strategies also tend to be very expensive and need to leverage funding from the local, state, and federal levels. That being said, the economic benefits of beaches—such as from tourism and flood protection—make such efforts worthwhile.

Diagram of the strategies used in regional sediment management. Upper left: beach nourishment in Santa Barbara County (Photo credit: Jenny Dugan); upper right: groin in Southern California (Photo credit: CA Coastal Records Project); bottom: stream bank restoration (Photo credit: Joe Pecharich, NOAA).

Regional sediment management will be even more important as sea levels rise. Beaches respond to sea-level rise by moving upward and inland; however, when the beach hits a barrier such as a seawall or rocky cliff, the beach cannot migrate inland and can be lost completely. The two main options to solve this problem are to 1) make space for the beach to migrate inland by removing or relocating coastal structures, or 2) nourish the beach with large amounts of sand. As sea levels rise, the demand for sand to nourish beaches is expected to rise as well. As part of my fellowship, I am working to estimate the amount of sand that might be needed to keep pace with sea-level rise and the sand sources that might be available. As is already the case, not every beach that needs sand will be able to get it, which makes regional sediment management that much more important!

As local governments update their plans for sea-level rise, it will help to build on the plans and frameworks established by regional sediment management plans to strengthen regional coordination and continue planning for the optimal use of our precious sand.

Third place photo in CA Coastal Commission 2010 Photo Contest: "Happy Kids, Bowling Ball Beach". Photo credit: Kurt Fuchs