Spring through fall is normally a busy time for scientific fieldwork in the U.S. Snow melts, seas calm, and classes pause for summer break, providing a reliable window for data collection. But ever since COVID-19 was declared a national pandemic, fieldwork has been among the litany of tasks to be put on pause. Arctic expeditions have been deferred, water quality monitoring has been delayed, and a laundry list of other long-term research projects, some dating back 50 years or more, are facing unprecedented data gaps.

As a California Sea Grant state fellow at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center (NOAA SWFSC), I have had a front row seat to these difficulties. I have been working with NOAA’s White Abalone Project, in which scientists work collaboratively to not only breed captive white abalone, but to then restore them to wild environments, also known as “outplanting”. White abalone’s tragic claim to fame came in 2001 when it became the first marine invertebrate to be listed as federally endangered. Nineteen years later, white abalone recovery is still a priority at NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and is the subject of a comprehensive recovery plan. During my time at NOAA, I’ve learned that the most important pieces of this recovery puzzle are the snail-loving scientists from all over California and beyond who devote their careers to putting this species back where it belongs.

Kathy Swiney of NOAA accepts a hand-off of a cooler full of millions of endangered white abalone larvae from an SCMI staffer.My introduction to this vital network of partners began with the breeding side. In March of 2020 I traveled to the Southern California Marine Institute with NOAA SWFSC Research Fishery Biologist Kathy Swiney to pick up freshly-spawned larvae, driven down earlier that morning from Bodega Marine Laboratory in a series of hand-offs. I learned that it takes a small army of partners in a race against time to ensure that millions of tiny white abalone don’t die in transport. Luckily this hand-off took place before COVID-19, but Bodega Marine Laboratory has had their own challenges figuring out how to breed abalone during a pandemic.

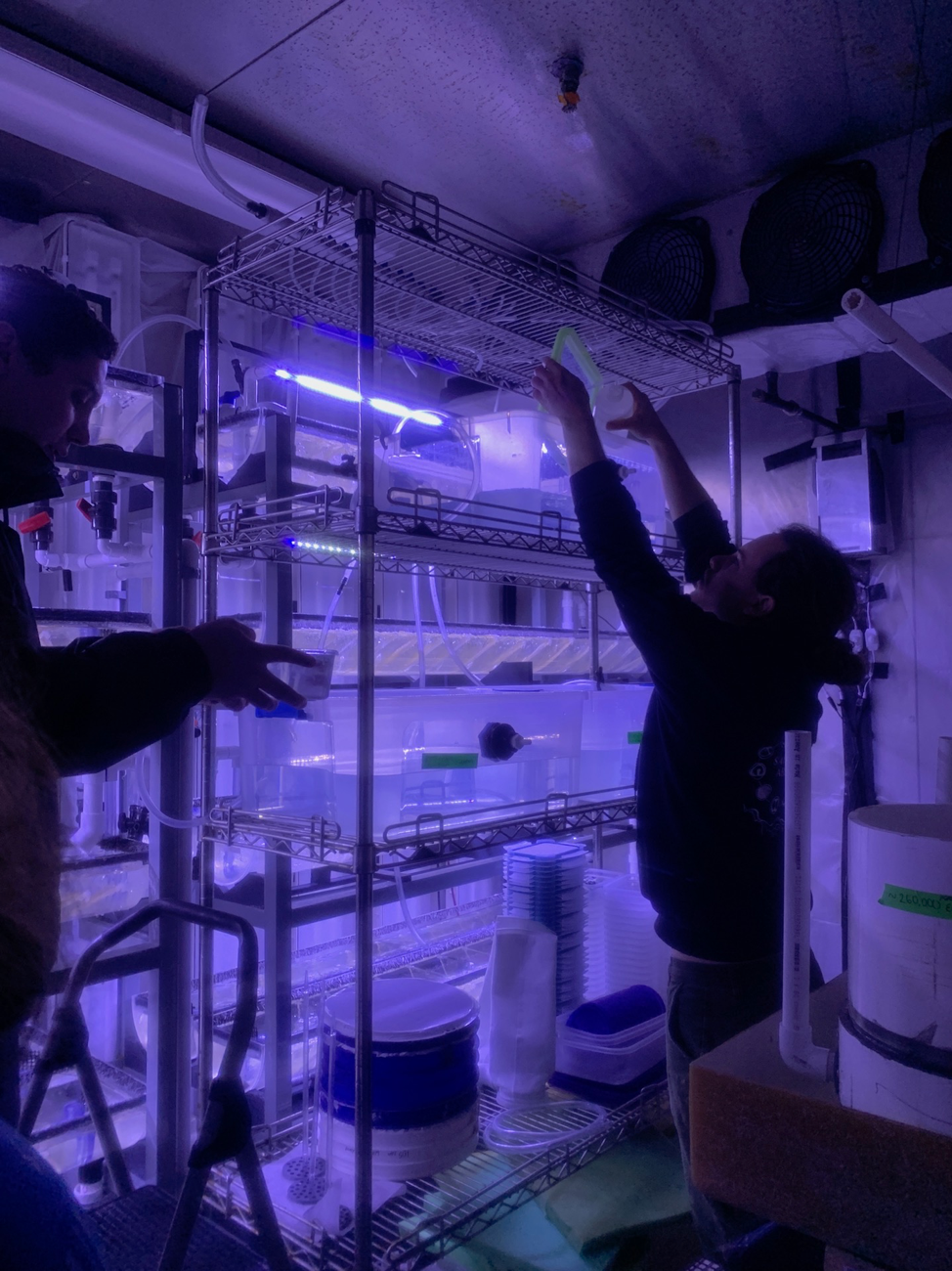

One week after transport, I joined in to help with “settlement day”. This is an exciting milestone, as it only occurs once the free-swimming larvae have survived long enough to settle to the bottom of their containers, becoming sessile. With help from our partners at California Department of Fish & Wildlife (CDFW), we scrambled to count and relocate the survivors to custom-made troughs. Our excitement was somewhat dulled by the recent news of stay-at-home orders. We stood awkwardly apart from each other by the tanks and wondered aloud about the efficiency of NOAA SWFSC’s air circulation system. A few days later, the building was completely locked down.

NOAA SWFSC staffers Zachary Skelton and Garrett Seibert work quickly to transfer abalone from larval buckets into custom troughs.The thing about captive baby abalone, in simple terms, is that if all goes well, they mature into adult abalone. The catch to this success is that older abalone take up resources and tank space from potential future generations of abalone. NOAA SWFSC and our captive breeding partners like Bodega Marine Laboratory excel at designing captive systems that maximize early growth and care, but these systems depend on the abalone being outplanted promptly upon reaching threshold size. While outplanting is no easy task under COVID-19 restrictions, it is also a crucial next step in white abalone recovery. It needs to occur both frequently and repeatedly to boost abundance in the wild, alongside habitat and predator surveys. For this labor-intensive part of the process we rely heavily on our partners, and thanks to them, 2019 was a wildly successful year for white abalone restoration. After years of experimenting with methods and sites with non-endangered red abalone, the project was able to outplant white abalone for the first time. 2020 was intended to be another important year of follow-up surveys and continued outplanting. However, it quickly became apparent that this would be a year unlike any other.

As spring became summer, COVID-19 took severe tolls on our project partners and their fieldwork abilities. Fewer staff allowed in facilities meant fewer hands to care for animals and to participate in field operations. Although some partners like the Santa Monica Bay Foundation continue to dive, the planned monitoring and outplanting for spring 2020 was never completed and resulted in a significant data gap. Unlike the Bay Foundation, NOAA SWFSC ‘s dive program was shut down completely, and approval to outplant was not received until September. This removed critical people from the project—NOAA’s closed-circuit rebreather divers. This special SCUBA certification allows researchers to considerably prolong their bottom time, thereby increasing their efficiency. Without NOAA SWFSC, it took the remaining partners 2-3 times longer than normal to accomplish tasks. This came at not only a greater expense to the program’s budget, which is funded almost exclusively through grants, but to the program’s safety. In addition to communication difficulties created by multiple socially-distanced vessels, smaller teams mean repeated dive-days and increased task loads, making the overall dive operation less safe.

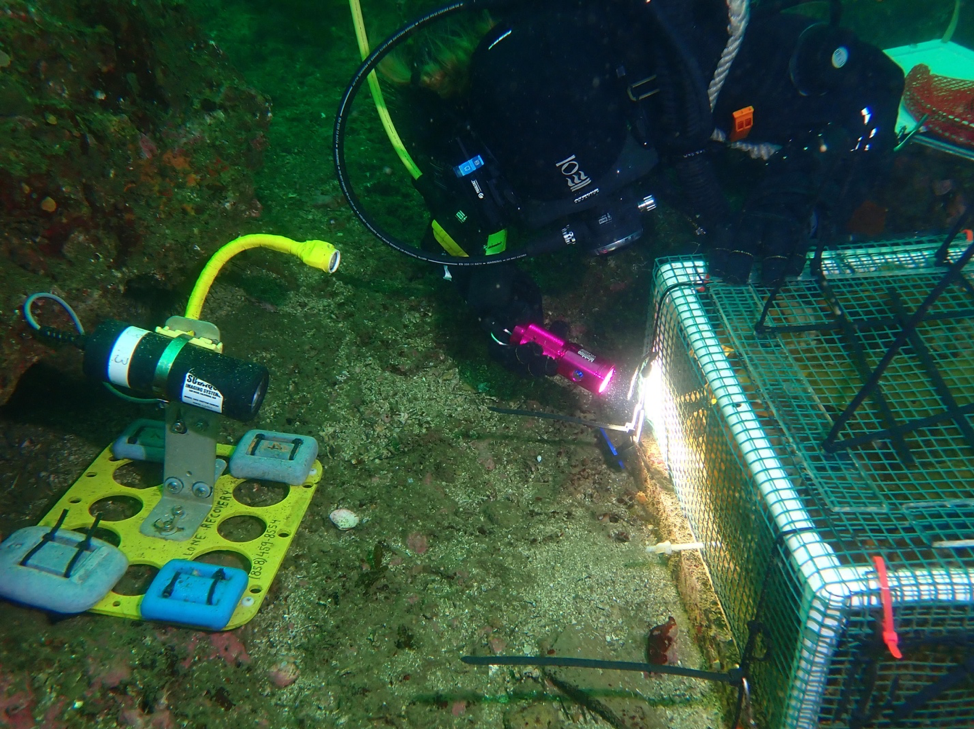

NOAA and partner researchers stock a Short-term Abalone Fixed Enclosures (SAFE) with juvenile white abalone off of San Diego. These SAFE modules are designed to exclude most predators and retain the abalone for a few weeks while they acclimate to their new environment. In a few weeks, divers will release them to natural reef. Photo by Bill Hagey, Pisces Design and NOAA volunteer diver.

Luckily, this team of professionals has avoided any safety concerns. This is where the coalition is both at an advantage and disadvantage. On one hand, as described above, raising white abalone takes a village. Having some partners able to outplant earlier than SWFSC has meant that the program was able to get rolling earlier than if it had been SWFSC alone. On the other hand, the program relies on every person in the village to be present, or else the safety and efficacy of the program are compromised.

NOAA SWFSC’s phased reintegration plan is closely tied to San Diego County’s COVID-19 caseload statistics, and we are all aware that there is a lingering threat that we could return to a lockdown. Luckily, the White Abalone Project has received approval to continue outplanting into December. Thanks to this hardworking team, white abalone have now been successfully outplanted into waters off of San Diego and Los Angeles for the second time in history. Jenny Hofmeister, an invertebrate program environmental scientist for CDFW, reports that monitors are also starting to see handfuls of survivors from last year. This supports a comment made to me by NOAA’s Senior Fishery Biologist Melissa Neuman, that “white abalone need a full team of partners in order to be restored”. Just as our fragile white abalone populations depend on a certain threshold of comrades to thrive, we too can find strength in numbers. We are both only as strong as our networks.

Another vantage point of researchers monitoring and stocking a SAFE. Photo credit John Hyde, NOAA SWFSC.

Watch footage from NOAA’s successful first white abalone outplant in 2019.